On the Shocking Difficulty of Getting a Doctor’s Note, and the Not-So-Shocking Difficulty of Getting Anything Done in a Bureaucratic System

Systems that meet everyone's needs, except the user's

I.

Nine months ago, I was heading to dinner with friends when I noticed a headache. Like any paranoid survivor of 2020, I wondered: was this covid? Was I exposing my friends? Should I ditch dinner, lock myself at home, and test until the headache goes away? Maybe. But everyone was vaxxed and, frankly, done caring about covid. Besides, my headache was mild. It could be allergies or a lack of sleep or nothing at all. I went to the dinner.

As we ate, the headache worsened and my covid paranoia ratcheted up. I promised myself I would test immediately upon getting home. Eventually, the pain grew loud enough that it drowned out the conversation. Losing track of what my friends were saying, I went into autopilot, offering “yeah true”s and “wow that’s crazy”s, hoping that the things being said were, in fact, true or crazy.

By the time I arrived home, the headache overrode everything else. I tore open a covid test. Negative.

The next day, the headache persisted, so I tested again. Still negative.

Over the next month, with the headache still rolling, I’d periodically test. I never tested positive, nor developed any other cold or fever symptoms. No cough, no congestion, no raised temperature. Just a dull-but-debilitating headache, and an accompanying inability to think.

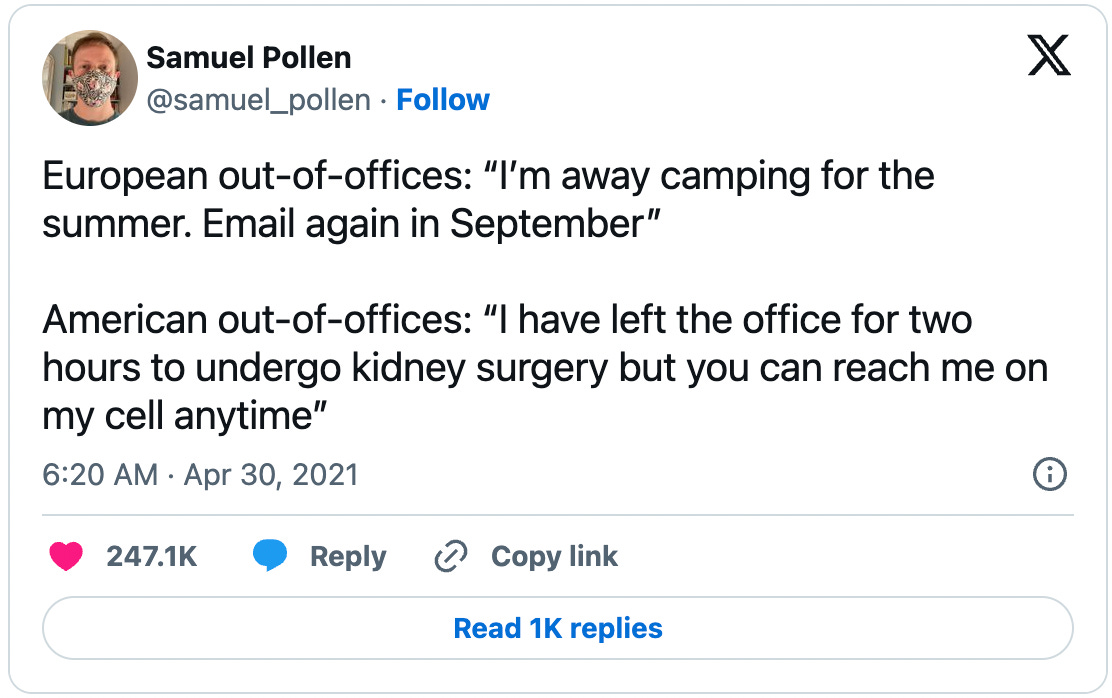

Ridiculously, I worked my normal job through this. Even more ridiculously, I did so of my own volition. My manager supported me taking time off, but no, I couldn’t let go of my American, I-should-work-through-this attitude. My headache would surely improve tomorrow, I thought. Neither rain, nor snow, nor sleet, nor hail, nor crippling neurological problems shall stop my toxic American work ethic.

Eventually, though, my headache got bad enough that I caved in and asked to go on medical leave.

Well, kinda. Still inexplicably optimistic that my headache would vanish, I requested to go on 50% medical time. I proposed working mornings, when the headaches were absent, and rest in the afternoons, when the headaches took over. My manager agreed.

The strange thing about asking for medical leave at my company: the request is handled entirely outside of the company. To avoid any impropriety — say, a manager rejecting a valid leave to squeeze work out of someone — my company requires all requests be handled by a third party. As such, my manager had no say over my leave. Instead, it needed to be approved by this impartial third party.

Unfortunately, this third party might be best described as “sloths stuck in their own red tape”. They take weeks to approve leaves, even though many people — probably most — need to go on leave immediately. My headaches were bad right then, but the third party needed time to unstick itself from its red tape. Paradoxically, I worked part-time while waiting for the third party to decide if I could work part-time.

Trying to spur the approval process, I called the third party. The third party’s support line was a smooth, effortless system that resolved the issue in minutes. Just kidding! It was the usual combo of inscrutable menus, a staticky endlessly-looping 30 second jingle, and a robotic voice saying “Your estimated wait time is forty eight to eighty seven minutes.”

When a representative finally answered, they referred to forms and policies using unrecognizable internal jargon. I tried to ask what the different forms and policies were, only to be interrupted with “You need a note from your doctor.” I tried to sneak in clarifying questions. Each time, I was cut off with: Can you get a note from your doctor? You’ll need a note from your doctor.

The jargon and interruptions were annoying enough. But worse, this third party rep thought I was a first-grader playing hooky with a fake cough. I had been talking with my doctor for months. She wholeheartedly endorsed my taking medical leave. She had even proposed it! Of course I could get a doctor’s note to this stupid third party.

II.

A month later, I was in a panic, unable to get a doctor’s note to the third party.

I had thought I was in the clear. My doctor had filled out the form supporting my medical leave, which the third party had received. Knowing this, I waited for my medical leave to be approved.

Then I received an email from the third party. Yes, they said, we have a form from your doctor.

But it was the wrong form. It was a form giving me permission to go on full medical leave, not part-time leave. It didn’t matter that my doctor obviously supported me taking 100% time off, and therefore was fine with me taking 50% time off. The forms are also virtually identical, making it easy from my doctor to see the second form and think “wait, I already filled this out.”

Regardless, the third party told me, your doctor needs to fill out the part-time medical leave form. As a kicker, the third party added: and if we don’t get that form in the next 4 days, your medical leave request will be rejected.

Why did they wait to tell me? It’s the doctor’s responsibility to fill out the form, the third party replied, so our process only requires we notify them. They seemed confused by the suggestion that my leave being rejected might be of at least minor importance to me.

Okay, I had four days to get my doctor to send one more one stupid form to the third party. How hard could that be?

Almost impossible, it turned out. Regrettably, my doctor’s organization requires all forms be sent by fax. No email, the organization decreed, because “faxes are more secure than email.”

In a way, they were right. The fax system they used was so secure, they were unable to successfully receive or send a single fax to or from the third party.

In hours-long phone calls with my doctor’s office, I tried to confirm that they had received the new form. The poor, beleaguered doctor’s assistant couldn’t find it. I signed up for eFax and faxed them the form myself. Confirming my worst suspicions, the assistant asked if the form had any identifying characteristics, because it was hard to find it in the giant pile of papers lying next to the fax machine.

Then, miraculously, hours before the deadline, my doctor’s office found an old version of the form, filled it out, and faxed it to the third party.

In a horrible reverse-miracle, the third party never received it. With hours left before the deadline, I spiraled into a panic, bordering on a full-blown meltdown. I desperately called the third party. Could I get an extension, I asked, if I gave them an explanation, or a note from my manager, or perhaps an extremely generous bribe? The deadline is what it is, the third party rep said flatly. If they didn’t have the form — which they didn’t — my medical leave would be rejected.

The deadline passed. I still didn’t have the form in.

After a bout of despair, acceptance set in. I mean, I had been working part time while I waited. So what would they do if my leave was ‘rejected’? They couldn’t get that time back, so the worst they could do was dock my pay. (With approved medical leave, I would be paid my full salary.) Or maybe if I was lucky, there was a way to appeal the decision. Neither would be great, but I could live with either.

Two days later, I didn’t have to live with either. My leave was approved.

It was approved because everyone ignored the rules. My doctor ignored the restriction (or possibly strong recommendation?) to send everything over fax, and sent me the completed form over email. I forwarded it to the third party a day after the deadline. When I called the third party to beg for leniency, the third party rep I got was understanding and cheerful. Oh, sure, we can leave a note on your file that you just got the doctor’s form in, they said. Shouldn’t be a problem.

And sure enough, my request for leave was approved, as though none of this had happened.

III.

When talking about this mess, many friends have said: they probably intentionally make the process hard so that employees don’t go on medical leave.

I’m sure there’s truth to this. Nobody in this process is incentivized to put more employees on medical leave. In that sense, yeah, there’s probably a skew away from ‘make the process user-friendly’ and skew toward ‘make it hard’.

However, I’m reminded of the words of Jennifer Pahlka, the founder of Code of America and former deputy CTO for… the whole United States? I guess it’s the US executive branch, but still, impressive. In her book, Recoding America, she writes:

When systems or organization don’t work the you think they should, it is generally not because the people in them are stupid or evil. It is because they are operating according to structures and incentives that aren’t obvious from the outside.

Citing a specific example in an interview with Ezra Klein, she says (emphasis mine):

I’ve seen so many people frustrated with government services, and they make a lot of assumptions about how that government service got to be the way it is. One example I spent a lot of time on was SNAP in California — Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program — where the application form was over 212 questions.

It took a long time to fill out. And so people naturally assume that this is done on purpose, that the people making the form must not want people to get SNAP. And, for example, there, that’s not really what was going on. California is a very pro-welfare state. There’s a huge number of incentives for local communities to sign people up for SNAP. It’s great for their economy. It’s great for getting people out of emergency rooms, for instance.

But there are just so many stakeholders in this that they all got to pile on their questions, and you ended up with something that was really, really burdensome. And it’s hard to see those incentives from the outside. That’s just one example of them. But our public servants are incented to do things that, if you look at them rationally, don’t make sense.

And this, I think, is what’s really going on.

In my attempt to get my medical leave approved, almost every person I interacted with was very supportive! In fact, multiple people broke the rules to ensure my leave was approved. The third party gave me an extension without my knowing, my doctor emailed the form despite being told to fax everything, and then third party just overlooked the fact that I technically missed an already-extended deadline. The people involved seemed to understand that my medical leave request was legit, and went out of their way to make it happen.

It was systemic rules, layered on at each step, that made everything hard. My employer doesn’t want to open itself to being sued by employees who feel their leave was unfairly rejected, so all leaves requests go through an extremely bureaucratic third-party. Someone, somewhere deemed faxes “more secure” than all digital technology, and so my doctor’s office still requires it. When my doctor needed to fill out a new form approving a 50% leave in addition to a virtually-identical one approving 100% leave, I guarantee it was required to reduce the risk of a lawsuit. In the US, it’s always about avoiding getting sued.

I understand these requirements. It’s reasonable to want to keep medical forms secure. It’s reasonable to want to avoid being sued.

But as these requirements pile up, the process becomes focused on them, rather than the people using the process. Tradeoffs between these requirements and usability go ignored in favor of maximally meeting the requirements. The process tries as hard as possible to avoid getting sued, rather than to be usable. Those on the inside — the lawyers, the policymakers — design the process to meet their needs, rather than those on the outside — the actual users.

As Pahlka says in her book (which, by the way, is a great read):

[Those building risk-averse government systems] consult every imaginable stakeholder, except the ones who matter most: the people who will use the service.”

I strongly suspect the same is true for this medical leave process. The endless customer service calls, the unrecognizable jargon, the extremely-similar-but-actually-different forms, the lack of communication about imminent deadlines: they all in aggregate scream, “we don’t talk to actual users.” Because in designing a process for those on the inside, you create one that’s impenetrable to everyone else.