Best Responses to "Maybe Treating Housing as an Investment Was a Mistake"

What to expect when you're expecting home prices to rise

I recently published a post, Maybe Treating Housing as an Investment was a Colossal, Society-Shattering Mistake. It got a lot of discussion online, so I want to highlight some of the most common and interesting comments. Forgive me if I missed a great comment of yours — there were too many to capture them all. This is especially true for Hacker News, where the article blew up after I had compiled a list of comments.

I.

viking_ says:

[Housing prices outpacing inflation] is very new. On average, inflation-adjusted home prices were flat over the entire 20th century: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Case%E2%80%93Shiller_index#/media/File:Case%E2%80%93Shiller_Index.svg

Housing can be a sort of investment, but not like stocks. It would be more like bonds, a hedge against inflation or loss of income. No matter what, you have a roof over your head. If your city doesn't go to shit, its value will remain relatively stable. You can downsize after your kids move out. If it does go up in price, great, but you shouldn't count on it.

The recency is definitely noteworthy, and I didn’t realize how recent the trend was. As the comment points out, the home price-to-CPI ratio is relatively stable from the 1950s to 2000. It only goes batshit in the run-up to the 2008 financial crisis, briefly collapses (although still higher than before), then goes even crazier the last 10 years:

Also, viking_’s version of ‘housing as an investment’ is totally reasonable. It’s not an investment that gains value like a stock portfolio. It’s an investment as a hedge against inflation, loss of income, and future rent increases.

But once housing prices are high enough, I think people can’t afford to think of ‘housing as an investment’ in these reasonable terms. If a down payment is most of your current life savings and a mortgage payment is most of your paycheck, buying a house isn’t a hedge. It’s an all-in bet. And it needs to gain value, not just keep pace with inflation.

Elsewhere, singularineet says:

Part of the reason people want to own a house instead of renting it is control. You can fix things when they break instead of being at a landlord's mercy. You can make your own determinations on price-vs-inconvenience when deciding on things. You can choose the color of the paint and deck out the living room like the bridge from Star Trek. You can be 100% sure you won't be evicted because the landlord wants to sell the place, or their cousin needs a place, or whatever. You can rent out a room. Nobody can barge in to poke around and check up on you. You can have big parties, big dogs, a waterbed. Etc.

Several comments echoed this sentiment. Choosing to buy a home is not just about financial gain. As one comment puts it, “Owning a home is much more than a coldly calculated ROI.” People want homes for personal reasons.

I completely agree that many people prefer to owning over renting, and that they’re willing to pay more for it.

But again, once home prices are high enough, homebuyers have to pay a lot for that preference. Look at that home price-to-CPI chart. The real cost of houses nationally has nearly doubled in the last 25 years. It’s even worse in cities like Los Angeles and San Francisco, where median home prices can be almost 10 times median income. If owning a home means going broke, you may not like the “coldly calculated ROI”, but you can’t ignore it. You need to do the math.

A common retort: just move somewhere cheaper. As horsawlarway points out:

There is land out there that is cheap as fuck-all. Lots of places will flat out hand you the deed if you promise to live there and build a house.

Some places will subsidize you moving into a house for $1. You just have to do it. Vermont and Ohio will literally PAY YOU to have you move into some areas (10k).

The problem is that young folks generally don't want to live in those locations. […]

If the US wants to alleviate housing costs, the most effective route I think we could go is to simply make it more appealing to live in rural areas. (ex: force those cable companies we paid billions to for rural broadband to go actually install rural broadband)

The whole "Californian diaspora" effect we got during covid is actually a wonderful example of the right way to do this.

I appreciate this comment because it points out an alternative — not everywhere is as expensive as coastal Californian cities! — while acknowledging that there are reasons people don’t want to move there.

Relatedly, people want to live in those expensive coastal cities because they can find jobs there. I think, and hope, that remote work will shift this. But you can’t be surprised when all the millennials want to live in New York and SF if all the jobs are there.

On the topic of expensive coastal cities, lmericle says:

The US has not established any new metro areas, let alone anything like a "big city", in the past 50 years. Which means everyone is still scrambling for exactly the same land as people were 50 years ago.

If new opportunities exploded out of some new cities willed into existence by federal direction of public and private spending, we wouldn't have the dearth of urban land we have today.

So… anybody wanna start a new city?

II. How Good is Alice’s Math?

The original post started off with our friend Alice deciding whether to rent or buy a house. She finds that — at least in certain situations — for buying to be worth it, housing prices need to outpace inflation.

A contingent of comments were very skeptical of this math. Some readers seemed to outright reject the article because they thought it didn’t add up. For example, in the Substack comments, Chris says:

The math fails to account for mortgage interest deduction on income taxes, and for increases in rent prices. […]

I'd be more persuaded to read the rest of the article if the math added up, but unfortunately it's not realistic. You paint a worse picture for home ownership than it deserves.

Andrew, also in the Substack comments, says:

It leaves a lot of reasons against home ownership too, like insurance costs, property taxes, maintenance costs, and most importantly the opportunity costs you pay on the downpayment, which could otherwise go into other investments.

So I want to clarify: Alice’s rent-or-buy choice does, in fact, take into account all of those factors.

More generally, Alice is using the NYT rent-or-buy calculator. Determining “which is better, renting or buying?” is a big, complicated financial question that depends on tax deductions, maintenance fees, how frantic Jerome Powell sounds, and a dozen other factors. That’s why Alice relies on the hard work of the New York Times, which accounts for all factors the comments complained about and more.

(Really, look at the calculator. It does a ton.)

In defense of these comments, I didn’t explicitly say the calculator covers all these factors. For any unspecified value, such as the property tax rate, Alice uses the reasonable-ish default values provided by the calculator. You could argue over some of them (and I’m sure people will), but defining all of them would have turned the post into an Excel spreadsheet. Still, it’s understandable that readers were confused.

Other comments disliked the values that were specified.

For example, Alice plans to live in the house for 18 years before selling. Bigzzzsmokes thinks that if Alice wants to do homeownership right, she’s gotta commit:

This article doesn't make fair comparisons as you only have the house for 18 years, knowing it takes 30 years to payoff. If you did a 30 to 40 year investment comparison, buying a home saves you the most money, and its not even close

Alice also assumes a 7% mortgage rate and 2% inflation. Maraxusx takes issue with this:

All the calculations are skewed to be the worst possible outcome for home ownership. 7% mortgage rate, 2% inflation, mild rent increases... It feels like a lot of propaganda to me.

You might say, "he's using 7% because that's close to what you might get a mortgage for today" to which I would say, then why use 2% inflation?? If inflation slows and the Fed drops rates in 5-10 years you can refinance at a lower rate. Meanwhile all that inflation took a shit all over your rental rate argument and it isn't coming down.

On the first point: 18 years seemed like a reasonable length of time to own a house (people often move when their kid goes to college, right?), but sure. Maybe owning for 30 years is more fair.

On the second point: I had reasons for these numbers1, but in retrospect Maraxusx is right and they could be better. It's weird to set a mortgage rate to 7% when they’re at that level now because inflation is high. I also agree that Alice could refinance at a lower rate.

As a sidenote, though, some comments suffer from recency bias over what’s ‘normal’. One comment suggested that because I wasn’t using a 2.9% mortgage rate, I “cooked the numbers.” This is crazy. Yes, you could get a 2.9% rate in 2020 and 2021. But that’s pretty much the lowest they’re ever been. It’s totally possible, but it’s not the norm.

So Alice tries to decide whether to rent or buy again. This time, to be principled and to placate angry internet commenters, she sticks to 30 year averages. Her new assumptions:

The house is still $703K; a comparable apartment is $2950 a month.

The mortgage rate is 5.6%, approximately the average 30 year-rate since 1992.

Inflation is the 30 year average of 2.5%.

Investment returns are 8%, even though the SP 500’s 30-year average return is 9.87% and hence this is putting a thumb on the scale in favor of buying. But she’s afraid that if she assumes a 10% return, the internet will yell at her.

She will live in the house for 30 years before selling.

She does a joint tax return. (This makes minimal difference, but in the original post, she has a partner and I demand consistency in the Good Reason Cinematic Universe.)

All other values — property taxes, maintenance, etc. — use the default provided by the calculator.

Alice enters those numbers, and... she breaks even when home prices and rent both grow at 3.7% a year.2 Less than that, renting is better. More than that, buying is better.

In short, housing prices (both home prices and rent) need to outpace inflation for buying to make financial sense for Alice.

Admittedly, she doesn’t need them to outpace inflation by quite as much. But the core conclusion is still the same. In this totally reasonable scenario using 30 year averages for everything, if home prices and rent just grow at inflation, renting is much more cost effective.

Moreover, I’m not saying buying a house is a dumb financial decision lol. I’m saying that it often is a smart decision because housing prices outpace inflation. If you remove that assumption and instead assume housing prices and rent only keep pace with inflation, suddenly the math looks shakier.

In another thread, tbos8 asks:

I have to wonder if this is an apples-to-apples comparison. Idk anything about Littleton but where I live, most rental homes are smaller townhouses or older places. Most new and/or large single family homes are bought. So the median purchase and the median rental might be very different size/quality of homes.

This is rock-solid criticism. I did my best to make them comparable — I limited both rentals and buying to single-family homes — but still, yes, there very well could be a difference. Given the scenario above, if Alice had to pay 10% more in rent to get a comparable house, then housing prices only have to increase 3.2% for buying to be worth it. Housing prices still need to outpace inflation, but it’s closer.

One final note. In all of this, I didn’t even entertain the possibility of housing prices slowing below inflation. It felt too implausible, which is probably telling in its own right. But for what it’s worth, if home prices and rent rise slower than inflation, renting is ludicrously better.

III. Does Japan Do It Better?

MakeTotalDestr0i says:

to have your mind blown go look at how Japanese don't live in used houses they build new ones and used ones depreciate like couches. it's a clear example of how a different society solved the problem.

u/cryms0n makes a similar point:

As someone who has lived a big part of their life in Japan, Housing outside any of the Tokyo or Osaka hotspots is often seen as a liability, no different than a car. Houses depreciate to near zero worth in about 25 years (which is the standard to which they are usually built, although newer builds with updated engineering compliances allow for far longer-lasting builds). The land is worth far more than the house, so many people demolish and re-construct rather than renovate.

Why does Japan have shorter building life-expectancies? As explained by u/orientpear:

In Japan, for the most part, buildings lose value (not land) over the course of a 30 year mortgage. This is due to many things but is largely due to Japan being very earthquake prone and construction standards are regularly updated for newer information and technologies. This means that most newer Japanese buildings are made to be safe even in severe quakes. But it also means that older buildings are too expensive to retrofit. Looking back at the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, the vast majority of casualties were due to the tsunami, not the quake.

According to this paper, Japanese houses do have a much shorter lifespan (38 years) than their US and UK equivalents (67 and 81 years, respectively).

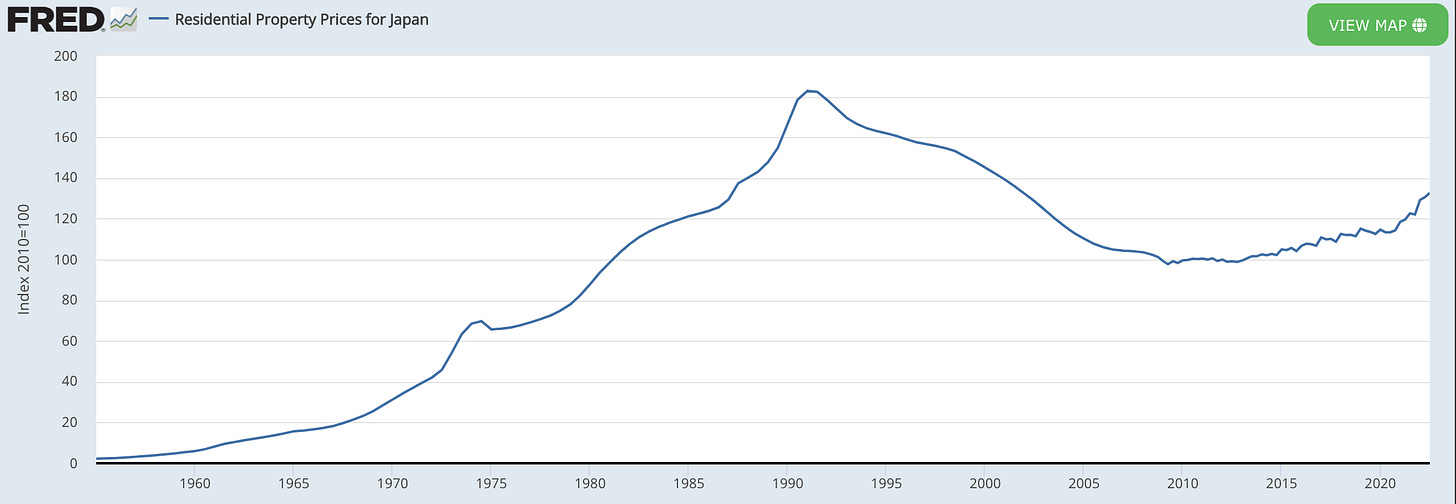

A cursory look at Japan’s housing prices also show that they have indeed declined over the last 30 years. However, the trajectory might tip you off that the decline isn’t just the result of Japan’s sensible housing policies:

What’s the deal with the peak in the early 90s? Mindaroth explains:

Huge asset bubble in the 80s formed for houses. It popped so badly that it’s still shaping the economy. That’s why no one values houses. They’ve already had their prices skyrocket and then crash catastrophically.

blkplrbr replies to this comment:

So Japan learned their lesson in a way that America refuses to?

Our housing bubble burst. For some reason we still assume that housing is an investment.

In response to that, Slim_Charles says:

I think it's less they learned a lesson, and more they simply never recovered from the crash. It would be like if the US housing market never recovered after '08, due to prolonged economic stagnation. The pyramid alluded to in the featured article collapsed in Japan, but the US economy has continued to grow and generate enough wealth to allow for the bag to continue to be handed down. Someone will be left holding at some point, but who knows when that will be.

I like this last comment in particular.

There’s cohort of people — no judgment, I’m among them — who fantasize about a market correction. Maybe you’re well-off but can’t quite afford a house in your area. Maybe you just think it’s bollocks that home prices are so high. So you fantasize about a 25-30% drop in housing prices that will allow you to finally buy a house and return a modicum of sanity to the housing market.

But the Japanese collapse shows the obvious: this fantasy comes with baggage. The housing pyramid scheme might turn out to be lode-bearing. Collapse it, and the economy might irreparably crumble too.

To that end, laxnut90 says:

Japan probably should not be used as an example of economics done well; at least not for the past 3 decades.

Their growth is abysmal and the average citizens are often struggling, especially in younger generations.

They also have a looming demographic crisis far worse than what we are experiencing in the US.

That “looming demographic crisis” is Japan’s aging and declining population. This chart, courtesy of CanAlwaysBeBetter, illustrates the difference between the US and Japan populations nicely.

Japan’s falling population, low birth rate, and migration to cities may cause rural towns to shrink or vanish. It’s a large enough problem that the Japanese national government pays Tokyo families to move to at-risk rural areas, with the payment tripling in 2023.

Knowing that, Japan’s flat home prices seem less impressive. With fewer total people who need homes, it’s easy to keep housing prices low. Even if Japan builds zero new homes, a shrinking population means housing supply can still outpace demand.

Japan didn’t solve anything, they just have unique circumstances that can’t be reproduced.

IV. It’s All About Zoning

Still, it seems noteworthy that Japan can replace housing so quickly. They’re out there tearing down and rebuilding houses like it’s nothing. Meanwhile, I’ve watched tumbleweeds roll around the vacant lot in my “one bedrooms are $3000 a month” neighborhood for seven straight years.

To that end, some commenters say other countries can still learn from Japan. From uber_neutrino:

[T]hey have a MUCH BETTER system for zoning and what you are allowed to do with land. It's very easy to knock down and build a new house with little to no BS to deal with (there is always some BS but in Japan it's minimal).

In response, Safe_Indication_6829 says:

We should copy Japan's zoning. Espically the part where it's national policy, not local policy. Local zoning has proved a disaster and we need the base zoning code and quotas for % of land allowing dense housing to vbe set at either the state level or the federal level in the US

BATMAN_UTILITY_BELT agrees, both that zoning is the problem and that Japan handles this better:

The issue is that there is a limited supply of housing due to zoning laws. Current homeowners are also incentivized to limit housing in order to protect their own investment. As a result, you get a society of people that own land and people that don't. It's a reversion to feudalism.

Zoning should not be subject to the democratic will of the people. Democracy is not always a good thing, especially if it creates a class of landless, property-less people and a nation of renters where people own nothing.

It's a shame there is no politician with balls that calls for stripping local communities of their ability to create barriers to entry when it comes to housing. It's literally the most anti-capitalist and ant-free market thing about the USA.

Japanese zoning laws and Singaporean public housing should be the models to follow.

This all jibes with me.

I do wonder, though, how much homeowners are consciously wielding zoning laws to drive up their home prices.

I recently had a conversation with a friend’s parents, who were going full NIMBY about their old hometown. Even though they don’t own a house there anymore, they live 30 minutes away and visit almost everyday. Developers were trying to build a big new set of condos, they complained. Traffic was already terrible. The condos will ruin the small-town vibe. There’s no rush to build so much, so fast. Naturally, they did what any good NIMBYs would do: go to a city council meeting and block development. They recounted this story as a victory for thoughtfulness and reason.

And while this conversation drove me crazy, one thing stood out. They have no financial incentive to block housing. They don’t own a house there anymore! No, they genuinely blocked housing because of traffic and small-town vibes.

So I wonder if some homeowners truly, genuinely believe that more housing has no impact on price. Maybe they’re housing supply denialists, but they come by it honestly.

Regardless, I agree that whatever the intent, the impact of zoning laws is to prevent construction and raise home prices.

captain_kinematics says there’s hope at least in some parts of the world:

This is exactly what is happening in the Canadian province of British Columbia; the provincial government is moving to reduce the zoning power of municipalities, citing basically the motivation you provide. Time will tell if it is wise and/or effective, but I’m cautiously optimistic, although as a general rule I’m not a fan of centralization of authority.

Relatedly, I would love to hear more how about other countries handle zoning and housing in general. There’s a whole world out there; surely some countries have successful models.

V. The Georgists

If you’re not familiar, Henry George was a guy in 1800s who thought that a lot of economic inequality came down to land. He proposed a Land Value Tax (LVT), in which government separated the cost of land from the cost of property, and taxed the value of land. His disciplines still exist today, roaming the internet like Reddit-based Jehovah’s witnesses to tell all who will hear:

Land value tax would fix this.

(Thanks to GeorgistIntactivist for the comment.)

As you can tell from its absence in the original post, my knowledge of Georgism is limited.

But upon reading more about Georgism after seeing the comments, I am sad I didn’t give it a shoutout. I believe a ton of society’s problems are downstream of housing. Moreover, I believe many of our housing problems arise from bad incentives — for example, blocking new housing can raise your own home’s value. As I understand it, Georgism and LVT claim to fix the incentives. From u/tony_montana_build:

The whole point of LVT is that it taxes the value of land, not whatever is built on the land. It punishes comparatively underdeveloped land like urban parking lots and single family housing in order to force density.

0m4ll3y says:

Because the location is the primary thing actually appreciating in value, land value taxes will stop a private landlord from getting that rental value and instead distribute it to society as a whole.

After cursory research, I’m intrigued. Georgists say economists from both left (Paul Krugman) and right (Milton Friedman) like LVT, although I can’t verify the quote from Krugman. I still do have niggling questions, like “would the land valuation process really not be captured landlords?” and “would landlords really not find a way to pass the taxes onto renters?” I know, I know — there are explainers out there for these exact questions. I will check them out. If you’re interested, you should too.

Semi-related to Georgism, Drinniol thinks it’s important to distinguish the cost of housing from the cost of land:

The article completely conflates houses as a physical good and housing as cost of land.

I know someone who lives in a very old and run down house in a desirable location. Their physical house is worthless - anyone buying it is going to tear it down and build a new one. Nonetheless, the "house" is still worth at least 600k from land value alone.

The scarcity isn't in the number of houses as physical buildings we can build. The scarcity is the space for those houses in the areas people want to live.

The article never touches this or even offhandedly mentions housing density and multifamily dwellings.

TheAJx responds:

It doesn't need to because the same principles apply. For any type of housing - whethere single family on a large plot or multifamily in a big city, incumbents are incentivized to oppose that because it impacts their “property values.”

I admit the original article lumps together house and land prices under ‘housing prices’. Still, the original article explicitly says that location — which is as close to saying ‘land’ without using the word — drives up the price.

I do, however, think that Drinniol’s distinction between ‘cost of house’ and ‘cost of land’ is a useful for possible solutions. In not thinking about “land” as a distinct category, I would have never dreamt up a land-value tax. Especially given the original post’s gloomy conclusion, I regret that I missed this as a possible solution.

On that note, MakeTotalDestr0i returns to offer motivation:

georgists just need to dream and scheme

Anyone who wants more affordable housing can take that advice to heart. Dream and scheme, baby, dream and scheme.

Honorable mention to TheSausageKing’s comment and jeremyhoffman’s response discussing the tax loop holes that benefit homeowners.

I picked 7% for the mortgage rate because it was the current 30 year mortgage rate. It was also below the long term average since 1971 — 7.75% — so it seemed like a reasonable estimate. However, looking at the full time series, it’s clear that this skewed by the 1970s and 80s.

I picked 2% for inflation because that the’s Fed’s target.

Some comments wanted a fixed rental price increase, often saying something like “rent rises at 5% annually”. It makes more sense to me to have rents move with housing prices, although they’re only partially correlated. Still, for what it’s worth, the average annual rental increase over the last 30 years is ~3.2%, based on Fed data and corroborated by this calculator.

I agree with you. We're caught in a terrible position where housing is both too expensive, but also needs to get *more* expensive so that middle-class people can pay back their investment.

I'm tempted to nitpick about the mortgage rates. They usually stay just above inflation, regardless of "average". On the other hand, there's lots of people who can't/don't refinance, and others who get bad rates, so there's a lot of people caught in that trap of paying a mortgage rate way higher than inflation. Those people really, really need housing prices to rise. And not many people stay in a house for 30 years, I think the average is less than 10 years.

The NYT calculator is great, but it's paywalled. Is there a free version?