On Corpspeak

Syncing Up, Circling Back, Learnings and Asks, Oh My

I. A Simple Ask

I was 23 when I found myself awash in corpspeak.

I had just started my first white-collar job. My coworkers were syncing up on action items and circling back to them later. They were saying that they didn’t have enough context, did anyone else have more context, Tom can you provide more context? They were pivoting to address the low hanging fruit; they were touching base about their recent learnings; they were escalating issues when they didn’t have bandwidth. They were taking things offline.

I didn’t understand why they used these words. Why sync up instead of meet? Why did people have bandwidth instead of time? Had we suddenly become computer modems and I didn’t realize it?

But more than confusing me, some words grated. This was especially true for words that seemed entirely unnecessary, like ask used as a noun (e.g., “I have an ask for you”) or learnings. At least bandwidth or sync up sounded kinda smarter. Ask sounded like a weird, non-committal version of request or an assignment. It was only one letter different from a perfectly valid alternative: task! Learnings sounded as though created by someone who, for arcane legal reasons, would be thrown in jail if they said lessons.

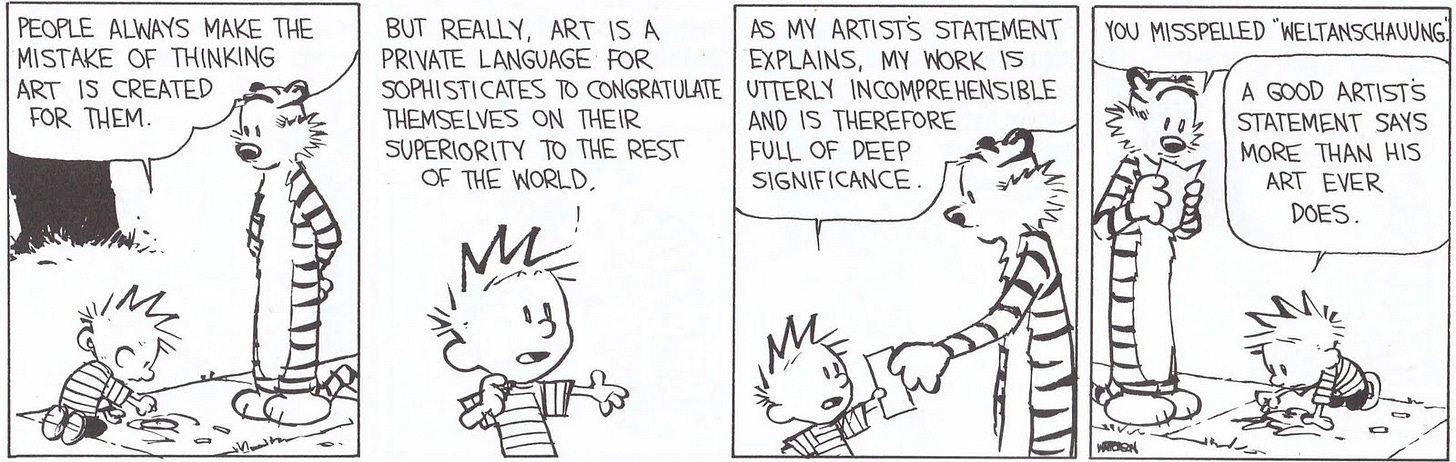

My whole childhood, I had seen books and films mock jargon generally and corporate life specifically. Calvin and Hobbes ridiculed the use of incomprehensible language to puff up meaningless ideas. Office Space, Fight Club, American Beauty, and I Heart Huckabees satirized the dreary emptiness of white collar life. Didn’t my coworkers realize how ridiculous this jargon sounded?

When I started working, I promised myself I wouldn’t become one of them. I would keep myself pure and use concrete, meaningful English comprehensible to the outside world. And god help me, I would strangle myself with a USB cable before I used ask as a noun.

Eleven years later, I now identify low hanging fruit and escalate issues and circle back to last week’s action items. So, yeah, I fully failed. But goddammit, I don’t use ask as a noun.

After all that time, though, I finally see why people do.

II. Discount Employees

A few years ago, I learned of an employee blow-up at large, well-known company. To keep confidentiality, I’ll change names, places, and details, but the key points of the story are completely true. Let’s call the company Company X.

Company X operates all across the US, so employees are paid in part based on where they work. Work in a place with a hot job market - say, New York City - the company pays you more. Work in a place where you’d be lucky to get a job - say, Detroit - the company pays you less.1 All Company X employees are aware that location affects employee pay. Everyone communally knows that you’ll get paid more in NYC than Detroit.

One day at Company X headquarters, employee Alice is going through some expense files on Dropbox. One file catches her eye: Location Compensation. She opens it to discover it discusses, very generally, how pay is set based on location. Again, all Company X employees know pay varies across locations.

But something about this file irks her. To distinguish where employees receive high pay versus low pay, Company X organized the locations into three bins: discount, national, and premium. New York City, naturally, is a premium location. Detroit is a discount location. One of her friends works in Detroit, and something doesn’t sit right about her friend being a discount employee.

So Alice makes a copy of the file and sends it to her friend Brenda in Detroit, who is even more incensed. Brenda sends it around to everyone she knows in the Detroit office, saying “FYI Company X thinks we’re discount employees. Love working at a company that values us <3 <3 <3.”

News spreads to other offices. Employees in other offices that think they might be discount locations get worked up. People start posting on internal message boards. The sentiment is all the same: a heavy, sarcastic “Feeling really valued rn”.

HR at Company X eventually gets wind of this and tries to shut it down. It’s obviously too late to stop people from knowing now, but they can still control the spread. Naturally, HR burns the evidence and deletes all the original files that mention discount, national, and premium locations from Dropbox. They create new files and double-check the permissions on them.

To be extra-extra safe, HR also renames the discount bucket to standard. Now, the buckets are standard, national, and premium.

HR will rely on common knowledge (within HR) that standard means cheap, and national means average, and premium means expensive. Even if anybody finds the file, it would be hard to throw a fit over being a ‘standard’ employee.

Again, while I’ve obscured some details here, the story is all true. At a large national company, there was a pay bucket called discount, people found it, got furious, so HR locked down the files and renamed discount to standard to stop it from happening again.

III. The Vagueness is the Point

Lots of people before me have noted that corporate jargon is riddled with euphemisms to hide nasty things. As the Atlantic notes, the corporate world is full of nice-sounding phrases to use in place of fire.

Streamline, restructure, let go, create operational efficiencies: All of these are roundabout ways of saying that people are about to lose their jobs.

Renaming discount locations to standard locations has the same effect: to hide the meaning of words and moreover, the negative feelings associated with them. It was not new information - all the Company X employees knew people in Detroit were paid less - but the emotional connotation of being labelled discount employees that caused the blow-up.

In fact, standard strips meaning and feeling so effectively that you might not even realize it was euphemism. Standard isn’t a lighter or more convoluted way of saying discount. It’s a word that conveys almost no meaning at all. Nothing about standard suggests ‘lower pay’.

In Succession, there’s storyline where two characters, Tom and Cousin Greg, are trying to figure out a slogan for their news network following a scandal. Originally they settle on “We Hear You”. They then discover that their company has an Amazon Alexa-like device that is literally listening when it shouldn’t be, making “We Hear You” a little on the nose. So they scramble to find a new slogan and eventually settle on:

As Cousin Greg describes the slogan:

It's good because, it's like, it's not clear exactly what the hell it means, so lots of wiggle room.

I think Cousin Greg is onto something. Corpspeak is not just about putting a pretty mask on an ugly face. It’s about wiggle room.

By using one-size-fits-all words and phrases that work whether the situation is fine or dire, you can avoid making it clear whether the situation is fine or dire. Consider a few corpspeak phrases:

I’ll escalate this could mean:

“I guess my manager should know about this.” OR

“I’m telling.”

Let’s take things offline could mean:

“Makes sense, we’ll figure out the details later.” OR

"Let’s never talk about this again.” OR

“If I have to talk about this with you for one more minute I’m gonna go apeshit in front of all these people.”

Tom, do you have more context? could mean either:

“Tom, were you around for the earlier meetings?” OR

“Tom, I have no idea what’s going on, please help me,” OR

“Tom, care to explain how you’ve fucked us over?”

If you have enough, well, context, you’ll know exactly what the speaker means. Often, though, you’ll only have a general idea what they mean or how annoyed they are.

And that’s the point! Corpspeak lets you talk about a shitty situation without making it 100% clear that there even is a shitty situation.

IV. A Taupe-Colored Feeling

That said, there’s more to corpspeak than *just* vagueness.

Take bandwidth, for example. When someone discusses whether “have the bandwidth to do something”, it’s pretty clear what they’re saying. They’re talking about whether they have the time to do it. So why do we say “I don’t have the bandwidth for that”?

Well, for one, “I don’t have time for that” sounds… harsh.

In the non-corporate world, saying “I don’t have time for that” often means “Ain’t nobody got time for that.” That connotation makes “I don’t have time for that” sound rude in an office environment.

Bandwidth, in contrast, only exists in the corporate space. It has none of the emotional dirt and grime words pick up when tossed around in the outside world. I don’t have the bandwidth for that sounds neutral, sterile. And if that still sounds a tiny bit rude, we can throw in an extra qualifier to make it even more neutral: I’ll check if I have bandwidth for that. (Don’t say that! You know you’t.)

Corporate language isn’t used only to paper over bad things. It’s meant to maintain certain, corporate-setting-appropriate feelings — feelings of neutrality, of equality, of technical sophistication, of harmony, of efficiency. Which yes, also means papering over bad things.

To that end, you can see the corporate appeal of bandwidth. It not only mutes the rudeness of “I don’t have time for that”, but also carries an air of technological sophistication and objectivity. It’s not that you don’t want to do it; you calculated the computational resources available to conclude you don’t have the bandwidth for it.

(Also, maybe vagueness does play a role. As described here by two talent development professionals - surely they know corpspeak! - bandwidth is used in place of “ability, aptitude, attention span, capability, capacity, competence, drive, energy, enthusiasm, intellect, interest, time, [or] willpower.” So the open-endedness allows the speaker to suggest they objectively can’t do something when they just don’t want to.)

Other corporate buzzwords similarly play up feelings. Touching base carries an aw-shucks, we’re-all-in-this-together feeling. Sync replaces meet because it feels efficient, high-tech. We’re not just meeting in some room, we’re synchronizing our mental states into a Six Sigma singularity.

Unfortunately, in order to create the preferred corporate environment feeling, corporate jargon does need to, you know, ignore a large chunk of the human experience. Reality is filled with opinions, hierarchy, fights, and fuck-ups. These grimy things get washed away by an jet-powered spray of neutralizing language, leaving only the desired corporate feelings. And, often, a vague feeling of emptiness.

V. Neutralisms

There’s a lovely little r/etymology thread about the origins of the noun form of ask. In it, one user comments:

[The noun form of ask] bugs me too. Maybe it bothers me that using ask as a noun is passive voice, like the request is disembodied. I'm not asking, the ask just appeared there!

But if I'm being honest I probably just dislike it because it's business speak.

These two reasons — disliking ask because it feels passive and disliking it because it’s corpspeak — are not mutually exclusive. In fact, I’d argue they’re one and the same.

Sure, it seems like a bad thing that ask is passive, that “the request is disembodied.” But a business setting might consider this a virtue.

Consider the obvious alternatives: request, task, assignment. Ever so subtly, these words convey information about the power dynamics at play. If I have a request for you, the power is in your hands to choose whether you do it. If I have a task or assignment for you, I hold the power. And in choosing a word, I reveal who has power.

Request or task conveys who has power; ask obscures it.

This, of course, is useful for creating the desired, neutral emotional state preferred by corpspeak. Hierarchy makes people feel bad, so why not do away with the words that remind us of it?

Words like ask are barely euphemisms; they’re more like neutralisms. The words they replace - request, assignment - aren’t ‘bad words’ in any way. Corpspeak just prefers to play it safe and strip out anything that might, somehow, somewhere, elicit bad feelings.

Recently, a coworker was creating a presentation that discussed “key learnings”. Why use learnings over lessons?

Lessons are something that someone - or maybe life - teaches you. Used in the wrong context, it might sound like someone messed up, and/or they were taught a lesson by someone who knew better than them. That hints at fuck-ups, or at least at hierarchy. Learnings has none of that baggage. As always, it sounds nice and neutral, like the knowledge just appeared out of thin air and floated into your mind.

This difference is *so subtle*. Learnings and lessons have the same definition. It’s just a difference in connotation. Corpspeak words are pod-people versions of their everyday equivalents: outwardly the same, but stripped of any soul.

VI. A Confession

This can sound conspiratorial, like there’s some shadowy cabal forcing people to use corpspeak. But no! It’s everyday people choosing to use it. Why?

Some reasons from my experience:

We’re social creatures, and we like to fit in.

If we dropped our unfiltered opinions all the time, we’d be fired.

It’s emotionally draining to honestly discuss fights, fuck-ups, and hierarchy in a productive way.

Point 3. sometimes looks like mutually-assured-destruction. We don’t say every thought in its purest form because we don’t want to hear all our coworkers’ thoughts in their purest forms. You might think Tom is a brown-noser, but Tom thinks you’re lazy. While it might be fun to tell Tom what you *really* think, hearing what Tom *really* thinks of you would be a huge bummer. Corpspeak lets you both say ‘whatever’ and get lunch.

Even in lower stakes situations, it’s taxing to talk about fights, fuck-ups, and hierarchy. When you use request or assignment, you have to think about whether you have power or not, and how the other people react to that power difference. If you openly say someone messed up, you’ll be on the receiving end of their anger. In many cases, using the vague, cagey language of corpspeak sidesteps all that.

To that end, I have a confession.

For all my railing on ask, I use action item all the time at work. If you haven’t used it, it means “something that a specific person should do.” It’s another term that replaces request and assignment, another term that clouds whether they have power in making them do it or not. So, yeah. Action item is just another version of ask. Despite my hatred of ask, I use action item all the time.

I use it partially because everyone around me uses it, sure.

But I also use action item because it’s easier. I often need to lay out tasks, requests, or whatever you want to call them. Some of them are assignments (I have power), and some of them are requests (they have power), and some of them are in a murky no-mans land between those two (the universe is an unknowable mystery). Often, I’m dishing out a mishmash of assignments and requests simultaneously. I can’t separate out which is which one-by-one. Instead, I use the vague, passive action item all the time so I don’t have to think about it.

VII. Acceptance

Articles like this often wrap up with a neat note saying We Should All Communally Agree to Stop Using Corporate Jargon and What a Better Place the World Would Be.

I agree, up to a point. Words that have perfectly acceptable normal variants are better. We can use meet instead of sync up. Nobody needs to use learnings. I think we should expand the acceptable-feeling-range in a white-collar workplace. We should be able to more genuinely acknowledge mistakes, hierarchy, inequality.

But I sometimes think some writer-types, including my past self, can’t see that corporate language will never be the same as traditional writing. They can’t be the same, because their goals are not the same.

Traditional writing strives to elicit feeling. Preferably strong, complex cocktails of sadness, joy, fear, disgust, lust, Schadenfreude, ennui, that feeling when someone cancels plans you didn’t want to do anyway. Really anything that speaks to the human experience. The stronger and more complex the feeling, the better.

Corporate language strives to limit feeling to a pre-approved range. It’s aiming for a nice La Croix of neutral, mildly positive feeling.

After years of working in corporations, I don’t think it’s fair to expect the goals of corporate language to match those of traditional writing. Again, yes, I wish corporate language would open the acceptable emotional range. Negative emotions are huge part of the human experience. If a workplace tries to act like they don’t exist, it’ll get a lot of pent-up, frustrated employees. I wish that leaders could level more with their employees.

But a work email is not a Jonathan Franzen novel. The goals are different. A work email is just trying to convey some information about problems in a way that doesn’t piss anyone off. A novel is trying to make you ask deep, fundamental questions about the human experience. If you felt that every time you opened a work email, you’d quit your job by 10 AM.

In the story where HR replaced discount with standard, it did so because employees genuinely lost their shit. And you kinda understand why! Sure, discount is the clear, meaningful word and standard is the vague, meaningless one. But it does feel shitty to know that your company, indirectly, via where you work, considers you a discount employee.

When I told her the story, my girlfriend argued that HR should have found a term that conveyed the meaning of discount without its negative feeling.

I think this is impossible. Employees in some locations are paid less than employees in other locations, and that kinda sucks for the lesser-paid employees to remember. Any word that accurately conveys the situation will also convey it kinda sucks.

You could call the worst pay bucket (discount) something neutral-to-positive like baseline and call every other pay bucket something even more positive like great and awesome and double-plus-awesome. But this is a textbook corpspeak move! Cast everything, including bad situations, into a neutral-to-positive light.

Using terms that carry meaning - and therefore also emotional weight - risks raising the emotional stakes. As a result, there’s no communal stopping corpspeak. We’re all choosing to use it, partially out of inertia but partially out of necessity. We don’t want the emotional stakes of our job to be high. We don’t want to risk coworkers blowing up at us. We want to get the information, and get out.

So, sure, use more understandable words where possible. But also make peace with corpspeak. Confusingly, frustratingly, terribly, we sometimes need it.

Covid, with remote work everywhere, threw a wrench in the works. Some companies have decided everyone everywhere gets paid the same; others are still clinging to the old world.

Great write-up on the way that corporate goals affect the language through the culture! Really enjoyed it, while also squirming in my chair. Here’s a couple additional thoughts that came up while reading it.

First, there’s the way that wider American culture affects these corporate goals. The great social psychologist Geert Hofstede identified several “cultural dimensions”, which reflect how different cultures handle the unavoidable facts of living together in large groups. He defined the dimension of “power distance” as “the extent to which the members of a society accept that power in institutions and organizations is distributed unequally”. (Note the word “accept”!) [https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-3-319-28099-8_1888-1]

While not lowest on the list, America rates towards the lower end of the scale on the social acceptability of power differences. In other words, we all know that power differences exist (especially in corporate environments!), but it’s super-rude to acknowledge them. Hence, “neutralisms”! [http://hopeinterculturalcomm.weebly.com/power-distance.html]

The second thought is closely related. At face value, your story about Company X’s “discount employees” illustrates how Americans handle power differences that become visible: social shaming by those with less power, followed by deliberate obfuscation by those with more power. But if that example really is typical (and I think that it is), it means that, in some way, everybody really got what they wanted! Workers called out the violation of a cultural norm, thereby establishing the validity of the cultural expectation. And the company got to “paper it over” with no real consequences. Mission accomplished!

If you’re like me in this regard, that observation feels really gross. Shouldn’t we want *actual* equality, instead of re-enforcing a culture where we all collude to ignore real de-valuation of human worth? Sure! But, as you correctly call out above, it’s easier this way.

Thanks for the post. Very thought-provoking!

There's a delightful Twitter thread about translation to corporate-ese:

https://twitter.com/MeanestTA/status/1509937547522318342

The person tweeting this noted, "Everyone on my team (5 men ages 48-75) texts me to make sure the slang they’re using is correct in context. ... In return they translate my frustrations into professional corporate."

An example they shared of one of those translations to 'corpspeak':

Me: “How do I say this meeting is a waste of my time I am not paid enough to deal with your bullshit?”

Boss: “Can you provide me with a meeting agenda so I can ensure my presence adds value? I want to prioritize my schedule to support our most urgent needs.”